-

Synopsis

-

Praise

-

Background

Synopsis

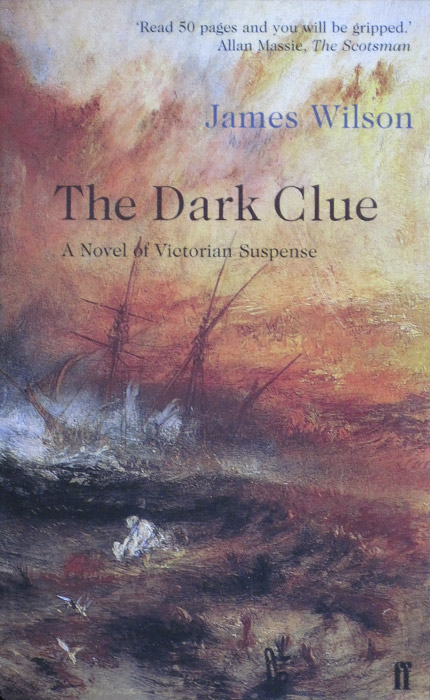

J.M.W.Turner was one of the boldest and most elusive geniuses England has ever produced. When Walter Hartright and his sister-in-law Marian are commissioned to write a biography of the great Romantic landscape artist, their attempt to draw his life out of the shadows sends them tripping across Victorian London in all of its staggering extremes.

Together they encounter a kaleidoscopic array of fantastic characters, from the hardened street urchins of the city's poorest quarters, to the tawdry women of the dockside brothels, to the celebrated visionary, John Ruskin. And yet the more Walter and Marian discover of Turner — the depraved company he kept, the dark places he frequented, his mysterious link to an unspeakable act — the more his true life seems to move vexingly out of reach. Can Walter and Marian untangle fact from a rapidly expanding web of conspiracy? What is the price of truth?

Praise for The Dark Clue

'The Dark Clue is James Wilson's first novel, and a remarkable one. It owes much to Wilkie Collins's masterpiece, The Woman in White, perhaps the greatest Victorian novel of suspense. Collins is not only Wilson's model: he has lent him two characters, the artist Walter Hartright and his sister-in-law Marian Halcombe, who here, as in Collins's novel, bear most of the burden of the narrative.'

'That said, Wilson hasn't written a pastiche Victorian novel, as, for instance, Charles Palliser did in The Quincunx. Indeed he has brought off something which is really very difficult: to write a novel set in the period when the greatest English novels were written, and to come up with something which is not an imitation but which never rings false.'

'Wilson has written a wonderfully entertaining novel. But it is not only entertaining; Walter Hartright is investigating the mystery of a life. In doing so, he must confront the mystery of the springs of art and the nature of genius.'

Allan Massie in The Scotsman

'His great achievement is that, as the story progresses, its texture increasingly resembles that of Turner's paintings: seemingly effortless yet immaculately designed and executed.'

Literary Review

'James Wilson's ambitious, intelligent and gripping first novel is about how we can never know the whole truth about a life. The Dark Clue is rich with atmosphere and suspense.'

Sunday Express

'Wilson's evocation of a mysterious London blanketed by smog is superb.'

The Financial Times

'It's a real thriller, I enjoyed it greatly. It was beautifully structured. I love London even more after reading this book.'

Brenda Maddox

'The Dark Clue explores the way in which we cling to formal structures and its beauty lies in how it undermines its own formal devices. Neither parody nor pastiche, it wrestles with the structure of Victorian detective-fiction from a modern perspective, setting the tightly-coiled spring of plot against the vortex-like coils of Turner's painting.'

The Times

'The author of The Woman in White recalled the painter standing at his easel, locked in some kind of synaesthetic reverie: "some wonderful dream of colour; every touch meaning something, every pin's head of colour being a note in the chromatic scale." In The Dark Clue, James Wilson has achieved something similar.'

The Independent on Sunday

'Another brand of British celebrity, from the 19th century art world, forms the background of a stunning first novel, James Wilson's The Dark Clue. Wilson tells his story in a stately narrative that recalls Collins and other masters of that era. Moreover, at moments his descriptions — of London's squalor, of exquisite English gardens, of the Thames on a foggy morning — are as luminous, majestic and mysterious as Turner's finest paintings; you may read them in awe.'

The Washington Post

Background

“ This is the edited text of a talk I gave about the novel at West End Lane Books in London.

It's always difficult to trace the genesis of an idea like this, but the first impulse, undoubtedly, was a long-standing fascination with the work of J.M.W. Turner. I would stand for hours gawping at his pictures in the Clore Gallery and the National Gallery. I found them immensely powerful — but also disturbing. Some of the things I found troubling were fairly obvious — the terrifying destructive power of nature in many of the pictures, or the artist's apparent difficulty in portraying the human figure (a puzzling lapse, given his prodigious ability to record inanimate objects). But there were also riddles and enigmas that I couldn't resolve, or even really identify, though I sensed they were there.

It was only when my friend Nicholas Alfrey — who is a Turner expert — took me round the Clore that I realized that Turner's life was every bit as strange as his pictures, and that there might be all kinds of odd connections between the two. Turner's mother went mad and died in Bethlem Hospital. Turner himself was rich and successful, but lived much of the time as a miserly recluse, in the most abject squalor. Contemporaries describe how the rain poured in through the broken skylights of his house, cascading over the masterpieces stacked against the wall — one of which was used as a cat-flap for the hordes of manx cats roaming the place and jumping on visitors' shoulders. The cats belonged to a deformed housekeeper, who kept her face wound in a scarf to disguise the cancer ravaging it.

And it wasn't just the housekeeper: Turner himself was astonishingly secretive. He hated being painted; he always travelled incognito; and it was only after his death that his friends discovered he'd spent his last years living in a cottage in Chelsea under an assumed name, with a Margate landlady called Mrs. Booth. The overwhelming impression is of a man determined to remain an enigma.

And in case you think I was just the victim of an over-active imagination, I wasn't the only person to be disturbed by Turner. Even during his own lifetime, he was known as the 'foremost genius of the age', and he is still considered by many people the greatest landscape painter in history. But, despite his reputation, he never received a knighthood (unlike many less gifted contemporaries), and was never made President of the Royal Academy. Even after his death, he was shabbily short-changed: the terms of his will were scandalously — and very publicly — disregarded by the government, which arbitrarily upheld the bits it liked, and overturned the bits it didn't; and, until very recently, if you looked for a blue plaque where he was born or lived most of his life, you looked in vain. (Contrast this with the house a few streets away where his contemporary Clarkson Stanfield lived, and which has proudly sported a blue plaque for decades. Stanfield was a good enough artist, but no one would have suggested he was the 'foremost genius of his age.') So England — or at least official England — was plainly not very comfortable with its greatest painter.

Most striking of all is the way Turner was treated by biographers. When he died, there was a widespread expectation that someone who had known him would immediately burst into print with a Life. Several contenders were mentioned — Ruskin; the critic and journalist Lady Eastlake; and Turner's fellow-artist George Jones — but, mysteriously, they all remained silent. At last, a hapless young journalist called Walter Thornbury blundered in where they feared, or declined, to tread, and produced a book that was universally reviled, in the most savage language. It's not the greatest biography in the world — but it's entertaining, and nothing like as bad as Lady Eastlake et al. would have us believe. So it's hard to escape the impression that his friends were all protesting a bit too much — that there was something they didn't want revealed.

I thought long and hard about how to approach the subject. Eventually — and very quickly — I came up with the startling idea of taking the hero of Wilkie Collins' The Woman in White, Walter Hartright, and setting him on Turner's trail. The Woman in White — a book I love —is generally credited with being the first, or one of the first psychological thrillers. In it, Collins explores his obsessions with concealment and truth and identity, and in Walter Hartright he creates a character who is past-master at uncovering secrets and conspiracies — so if anyone could get at the truth about Turner, he could.

But I also chose to use Walter Hartright for another reason. Turner was born in 1775, the year the American War of Independence started, and died in 1851, the year of the Great Exhibition. The world that formed him, therefore, was essentially Georgian and Regency and early Victorian — a world of wars and national crises and moral loucheness. The Woman in White was published in 1860, and its world seems to me very different — a high Victorian, pre-Raphaelite world obsessed with mediaevalism and chivalry. In sending this chivalrous knight in pursuit of a figure from the first half — in colliding these two worlds, and seeing what happened — I felt I was dramatising the great gulf in English culture in the middle of the nineteenth century.